(4 of 8)

From Speer's IMT testimony: The work camps were established so that long trips to the factories could be avoided and in this way permit the workers to arrive fresh and ready for work. Furthermore, the additional food which the Food Ministry had granted for all workers, including the workers from concentration camps' would not have been received by these men if they had come directly from big concentration camps; for then this additional food would have been used up in the concentration camp. In this way, those workers who came from concentration camps received, in full measure, bonuses that were granted in the industry, such as cigarettes or additional food. My co-workers called my attention to this fact [that the workers from concentration camps had advantages if they worked in factories], and I also heard it when I inspected the industries. Of course, a wrong impression should not be created about the number of concentration camp inmates who worked in German industry. In toto, 1 percent of the labor personnel came from concentration camps. Of course, when on inspection tours of industries I occasionally saw inmates of concentration camps who, however, looked well fed . . . .

I learned, when I inspected industries at Linz, that along the Danube, near the camp at Mauthausen, a large harbor installation and numerous railroad installations were being put up so that the paving stone coming from the quarry at Mauthausen could be transported to the Danube. This was purely a peacetime matter which I could not tolerate at all, for it violated all the decrees and directives which I had issued. I gave short notice of an impending visit, for I wanted to ascertain on the spot whether this construction work was an actual fact and request stoppage of the work. This is an example for giving directives in this field even within the economic administrative sphere of the SS. I stated on that occasion that it would be more judicious to have these workers employed during wartime in a steel plant at Linz rather than in peacetime construction.

My visit ostensibly followed the prescribed program as already described by the witness Blaha. I saw the kitchen barracks, the washroom barracks, and one group of barracks used as living quarters. These barracks were made of massive stone and were models as far as modern equipment is concerned. Since my visit had only been reported a short time in advance, in my opinion it is out of the question that big preparations could have been made before my visit. Nevertheless, the camp or the small part of the camp which I saw made a model impression of cleanliness. However, I did not see any of the workers, any of the camp inmates, since at that time they were all engaged in work. The entire inspection lasted perhaps 45 minutes, since I had very little time at my disposal for a matter of that kind and I had inner repulsive feelings against even entering such a camp where prisoners were being kept.

No, I could not do that [learn about the working conditions in the camp], since no workers were to be seen in the camp and the harbor installations were so far from the street that I could not see the men who were working there. Naturally I had the utmost interest along this line [that a healthy and sufficiently trained labor supply should be at my disposal] even though I was not competent for this. As from 1942 we had mass production in armament, and this system with assembly-line workers demands an extraordinary large percentage of skilled workers. Because of drafting for military service, these skilled laborers had become especially important, so that any loss of a worker or the illness of a worker meant a big loss for me as well.

Since a worker needed an apprenticeship of 6 to 12 weeks and since even after this for a period of about 6 months a great amount of scrap must be allowed for-for it takes about that much time before quality work can be expected-it is evident that the care of skilled workers in industry was an added worry for us.

A change in the workers, in the way in which it was described here [through extermination by work], cannot be borne by any industry. It is out of the question that in any German industry anything like that took place without my hearing about it; and I never heard anything of that sort.

No, not in that form [used SS and Police against recalcitrant workers], for that was against my interests. There were efforts in Germany to bring about increased productivity through very severe compulsory measures. These efforts did not meet with my approval. It is quite out of the question that 14 million workers can be forced to produce satisfactory work through coercion and terror, as the Prosecution maintains.

From Speer's Spandau Draft: Goering showed his true colors at once. Instead of calling Sauckel to task as he had promised, he immediately launched a violent attack against his own Secretary of State, Field Marshall Milch, who by prior arrangement was the one who raised our objection to Sauckel's labor-bookkeeping. How could Milch accuse that good party comrade Sauckel, who worked so hard for the Fuehrer, of wrongdoing, Goering thundered. Ironically, it was he who only two days earlier had proposed ur strategy od spearheading our general attack with an objection to Sauckel's fantasy-figure reports to Hitler.

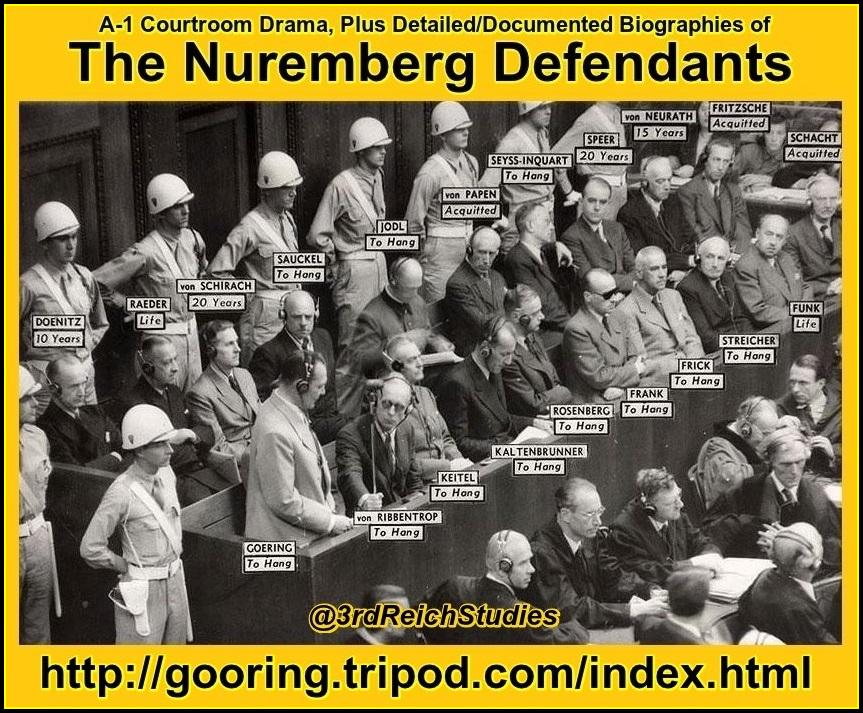

And Himmler immediately joined the stifling of our initiative. "Isn't the most likely explanation for the million missing bodies that they are dead?" he asked equably. It was only when I learned in Nuremberg of the numbers of dead in the concentration camps that I understood what he meant.

From Messerschmitt's US SBS interview: The ME 262 had a maximum speed of 560 miles an hour at level flight, both at altitude and near the ground. Its normal speed was approximately 500 miles an hour. The individual motors supplied for this aircraft varied markedly in efficiency. Due to difficulties with workmen and machines the airframes were inferior. Professor Messerschmitt was working on a specially built 262 with which he expected to achieve a speed of 575 miles an hour. The aircraft was capable of two hours flight at 27,000 feet without belly tanks. Professor Messerschmitt believed that conventional motors and propellers were satisfactory for designs involving speeds up to 500 miles an hour. Beyond that and until the speed of sound had been achieved, he believed a turbo-jet was the best type. For speeds in excess of sound, he had no definite opinion. (SBS)

April 22, 1943: From notes of the thirty-sixth meeting of the Planning Board:From Speer's IMT testimony: It can be elucidated very briefly. This is proof of the fact that the conception "armaments" must be understood in the way I have explained, because the two sectors from which the 90,000 Russians employed in armaments originated, according to this document, were the iron, steel, and metal industries with 29,000; and the industries constructing engines, boilers, vehicles and apparatuses of all sorts with 63,000 . . . .

That [the order that the deputies of the Reich Minister for arms and munitions are to be admitted to prisoner-of-war camps for the purpose of selecting skilled workers] was a special action which Dr. Todt introduced on the strength of an agreement with the OKW. It was dropped later, however. I believe that [the above] has been wrongly translated. It should not say "munitions industry"; it should say, "The armament industry received 30 percent." . . . But this is still no proof that these prisoners of war were employed in violation of the Geneva Prisoner of War Convention, because in the sector of the armament industry there was ample room to use these workers for production articles which, in the sense of the Geneva Prisoner of War Agreement, were not armament products. However, I believe that in the case of the Russian prisoners of war, there was not the same value attached to strict observance of the Geneva Convention as in the case of prisoners from western countries . . . .

As far as I know, French prisoners of war were not used contrary to the rules of the Convention. I cannot check that, because my office was not responsible for controlling the conditions of their employment. During my numerous visits to factories, I never noticed that any prisoner of war from the western territories was working directly on armament products ... the allotment of prisoners of war, or foreign workers, or German workers to a factory was not a matter for me to decide, but was carried out by the labor office, together with the Stalag, when it was a question of prisoners of war. I received only a general survey of the total number of workers who had gone to the factories, and so I could get no idea of what types of labor were being employed in each individual factory.

From Speer's IMT testimony: Beginning with the middle of 1943, I was at odds with Sauckel over questions of production and about the insufficient availability of reserves of German labor. But that has nothing to do with my fundamental attitude toward Sauckel's work . . . .

Those workers [the 50,000 skilled workers] had been working on the Atlantic Wall. From there they were transferred to the Ruhr to repair the two dams which had been destroyed by an air attack. I must say that the transfer of these 50,000 workers took place without my knowledge, and the consequences of bringing 50,000 workers from the West into Germany amounted to a catastrophe for us on the Atlantic Wall. It meant that more than one-third of all the workers engaged on the Atlantic Wall left because they, too, were afraid they might have to go to Germany. That is why we rescinded the order as quickly as possible, so that the French workers on the Atlantic Wall should have confidence in us. This fact will show you that the French workers we had working for the Organization Todt were not employed on a coercive basis, otherwise they could not have left in such numbers when they realized that under certain circumstances they, too, might be taken to Germany. So these measures taken with the 50,000 workers from the Organization Todt in France were only temporary and were revised later. It was one of those mistakes which can happen if a minister gives a harsh directive and his subordinates begin to carry it out by every means in their disposal . . . .

I do not deny that a large number of the people working for the Organization Todt in the West had been called up and came to their work because they had been called up, but we had no means whatsoever of keeping them there by force. That is what I wanted to say. So if they did not want to work, they could leave again; and then they either joined the resistance movement or went into hiding somewhere else.

From Speer's US SBS interview: In the case of the Moehne, it was the water supply of the Ruhr that was principally concerned. The attacks—which were also directed against the Sorpo and another small dam—indicated an intention to flood the Ruhr valley and destroy the summertime drinking water supplies of that area. The plan was excellent and might well have been expected to paralyze the Ruhr area. That it did not succeed was due only to the fact that the Moehne valley basin emptied and we were able to pump water from the other side of the Rhine at that time. The English probably did not know that as yet. The flooding filled the pumping stations in the power plants with mud, several units were soaked and had to be dried; this took weeks, but constituted no special loss for the industry. The Edor dam and the power plant below it is of no special importance as a source of power, but serves to regulate the water level of the Wesor for ship traffic. The attack was of little importance to us, and we did not understand what reasons lay behind it. Other than these two we never experienced attacks on power generating plants. (SBS)

From Speer's IMT testimony: After the attack on the Moehne Dam and the Eder Dam in April and May 1943, I went there and in that period I ordered that a special group from the Organization Todt should take over the restoration of these plants. I did this because I also wanted the machinery and the technical staff on the spot. This special group right away without asking me brought the French workers along. This had tremendous repercussions for us in the West because the workers on the building sites on the Atlantic Wall, who had up to that time felt safe from Sauckel's reach.

June 2, 1943: Rudolf Wolters, Speer's friend and archivist, meets Speer's parents in their Heidelberg home. From Wolters' diary:From Messerschmitt's US SBS interview: In June 1943, Professor Messerschmitt took the matter up personally with Hitler. He was then disturbed about the program for production of V-weapons. Messerschmitt explained to Hitler that, in his opinion, unless a production of 80- to 100,000 V-weapons per month could be achieved, the entire program should be scrapped. He argued that 50 per cent of the V-weapons would be ineffective. Messerschmitt felt that it would be possible for Germany to build 100,000 V-weapons a month when the US was capable of building 4,000,000 automobiles a year. He urged Hitler that one thing or the other should be done; either V-weapons should be produced in overwhelming quantities or everything should be done to build up the Luftwaffe. In Messerschmitt's personal opinion, if the Luftwaffe were not strengthened the war would be lost . . . . As a result of his insistence upon increased aircraft production in many Air Ministry meetings ... several of Messerschmitt's friends warned him to be careful or he might be sent to a concentration camp. (SBS)

June 26, 1943: Goebbels speaks at the opening of the 7th German Art Exhibition:From Speer's IMT testimony: But here again I must add something. This report is dated June 1943. In October 1943 the whole of the Organization Todt was given the status of a "blocked factory" and thereby received the advantages which other blocked factories had. I explained that sufficiently yesterday. Because of this, the Organization Todt had large offers of workers who went there voluntarily, unless, of course, you see direct coercion in the pressure put on them through the danger of their transfer to Germany, and which led them to the Organization Todt or the blocked factories. That [the workers were kept in labor camps] is the custom in the case of such building work. The building sites were far away from any villages, and so workers' camps were set up to accommodate the German and foreign workers. But some of them were also accommodated in villages, as far as it was possible to accommodate them there. I do not think that on principle they were only meant to be accommodated in camps, but I cannot tell you that for certain.

July 8, 1943: From a letter to Speer from the OKW:From Speer's US SBS interview: The first heavy attack was that against Hamburg. The attack against Hamburg caused me great concern that our production might be handicapped by a speedy continuation of similar attacks. Losses in Hamburg were very heavy then, the greatest we had ever suffered through air attack, mostly because of burning houses. The population was extraordinarily depressed. Loss of production in some places seemed to be very heavy. After this attack I went to the Fuehrer to tell him that it would be a great shock to armament production if we were to get about 6 or 8 such attacks against big cities. The effect of this attack consisted less in actual damage than in shock, and it may have been the mistake of all the attacks before and after Hamburg that they conditioned us systematically for air attack. That can be said as well for all previous attacks which were being increased as for the attack; against Hamburg which never reoccurred that severely. Hamburg remained a special case for a long time. (SBS)

July 27, 1943: Goebbels' Diary:From Speer's US SBS interview: At the first Schweinfurt raid we weren't prepared and so we were badly frightened by the results of this raid. As a matter of fact this raid had a serious effect on us. Aiming was good, and production at Schweinfurt was nearly paralyzed. At that time our only reserves consisted in the fact that the so-called 'Verlauf' for ball-bearings consisted, on the average, of several weeks' supply and that we reduced this 'Verlauf' after the first raid to eight days ... 'Verlauf' is the amount of ball-bearings that is enroute from the ball-bearing plants to the producers. Thus, if the ball-bearing plants were hit, the 'Verlauf' continues into production. So we were able to add the production of half a month to the available production. Beginning with this raid, because of the reduction of the 'Verlauf' to only eight days, occurred that some tanks and airplanes could not be finished due to the lack of ball-bearings. In these cases we had to haul ball-bearings by truck using soldiers as couriers. (SBS)

August 22, 1943: Hitler orders Heinrich Himmler to utilize concentration camp workers for A-4 production and decides to shift some prisoners from Buchenwald to Nordhausen.From Hermann Goering's IMT testimony: I knew of the subterranean works which were near Nordhausen, though I never was there myself. But they had been established at a rather early period. Nordhausen produced mainly V-1's and V-2's. With the conditions in Camp Dora, as they have been described, I am not familiar. I also believe that they are exaggerated. Of course, I knew that subterranean factories were being built. I was also interested in the construction of further plants for the Luftwaffe. I cannot see why the construction of subterranean works should be something particularly wicked or destructive. I had ordered construction of an important subterranean work at Kahla in Thuringia for airplane production in which, to a large extent, German workers and, for the rest, Russian workers and prisoners of war were employed. I personally went there to look over the work being done and on that day found everyone in good spirits. On the occasion of my visit I brought the people some additional rations of beverages, cigarettes, and other things, for Germans and foreigners alike. The other subterranean works for which I requested concentration camp internees were not built any more.

From Speer's IMT testimony: It soon became clear that it was Himmler's intention to gain influence over these industries and in some way or other he would undoubtedly have succeeded in getting these industries under his control. For that reason, as a basic principle, only part of the industrial staff consisted of internees from concentration camps, so as to counteract Himmler's efforts. And so it happened that the labor camps were attached to the armament industries. But Himmler never received his share of 5 to 8 percent of arms, which had been decided upon. This was prevented due to an agreement with the General of the Army Staff in the OKW, General Buhle.

September 2, 1943: From a Hitler decree concerning the concentration of the war economy:From Speer's IMT testimony: Immediately after taking over production in September 1943, I agreed with Bichelonne that a large-scale program of shifting industry from Germany to France should be put into operation, according to the system I already described. In an ensuing conference, Bichelonne stated that he was not authorized to talk about labor allocations with me, for Minister Laval had expressly forbidden him to do so. He would have to point out, he said, that a further recruitment of workers on the present scale would make it impossible to adhere to the program which we had agreed upon. I was of the same opinion. We agreed, therefore, that the entire French production, beginning with coal, right up to the finished products, should be declared as "blocked industries." In this connection both of us were perfectly aware of the fact that this would almost inhibit the allocation of workers for Germany, since, as I have already explained, every Frenchman was free to enter one of these blocked factories once he had been called up for work in Germany. I gave Bichelonne my word that I should adhere to this principle for a protracted period, and, in spite of all difficulties which occurred, I kept my promise to him.

September 6, 1943: From a document signed jointly by Speer and Funk:From Adolf Hitler, by John Toland: He [Himmler] was like Brutus, forcing his colleagues to dip their hands in Caesar's blood. The Final Solution was no longer the burden only of Hitler and Himmler but theirs [the Reichsleiter’s and Gauleiter’s], a burden they must carry in silence.

Bormann closed the meeting with an invitation to lunch in the adjoining hall. During the meal Schirach and the other Gauleiter’s and Reichsleiter’s wordlessly avoided each others eyes. Most guessed that Himmler had only revealed the truth so as to make them all accomplices and that evening they drank so much that a good number had to be helped to the train that was taking them to Wolfsschanze. Albert Speer, who had addressed the same audience just before Himmler, was so disgusted by the drunken spectacle that the next day he urged Hitler to read his party leaders a lecture on temperance.

Speer claims to this day [1976] that he knew nothing of the Final Solution. Some scholars have accused him of attending Himmler's speech since during it the Reichsfuehrer specifically addressed him. Speer insists he left for Rastenburg immediately after his own speech. Field Marshal Milch confirmed this [to Toland while he was writing the book]. Granted that Speer was not present, it is difficult to believe he did not know about the extermination camps. From the text of Himmler's speech it is clear that he thought he was talking directly to Speer--and assuming that he was one of the high-ranking conspirators.

From the affidavit of Walter Rohland: As the Gauleiter were scheduled to confer with Hitler in Rastenburg the next day and Speer feared that by that time our addresses would have dissipated, we drove to Hitler's HQ that same day in order to convince him of the urgency of our demands and the need for him to be tough with the Gauleiter. This is what I wrote a year ago, without having communicated with Speer about it in any way. Our trip took place in Speer's fast Mercedes which he drove himself. We left Posen after a snack and arrived at Hitler's HQ just after dark . . . . I declare under oath that the above information, given from my best recollection, is the truth. Signed, at Ratingen, July 6, 1973.

From the affidavit of Harry Siegmund [administrative aide to the Gauleiter of Posen]: I remember clearly that Speer left [Posen] in his car shortly after lunch. As I was responsible for organization and protocol, I was in constant touch with the hotel's director to make sure that everything would go off smoothly. I was therefore informed about all arrivals an departures. I also recall that when, in the course of a conversation on a later occasion with the liaison officer of the local army command, Prinz Reuss XXXVII, we compared Speer's cool presentation of the armament situation with the ominous rumors about Himmler's speech, Prinz Reuss emphasized that Albert Speer was not present during this speech . . . . [Himmler was extremely shortsighted] I would therefore doubt that Himmler during his speech could have noticed who was present, especially since, considering the 'Romanic' style of Posen Castle, bright lights were avoided. I declare on oath that the preceding statement, made from my best recollection, is the truth. Badenweiller, October 22, 1975.

Note: In 1978, Speer will answer these charges in the German periodical Controversies, edited by German historian Adelbert Reif. Nine years later, Speer's biographer, Gitta Sereny, will find Speers first draft of his 'Reply' in his papers. Twice as long as the published version, it also contains four more argument/explanations:Gitta Sereny, in Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth writes: The fact is that the more Speer tries to explain away awkward facts [about Posen], the clearer it is that he is trying desperately to avoid facing the truth. There is simply no way Speer can have failed to know about Himmler's speech, whether or not he actually sat through it. I believe that this was the turning point in his relationship with Hitler, even though it took a long time for it to be a complete reversal—if it ever was.

October 9, 1943: Goebbels records his thoughts on Himmler's October 6 speech in Posen, at which he was in attendance. From Goebbels' Diary:From Speer's IMT testimony: Generally speaking one can say that in the end every article which in wartime is produced in the home country, whether it is a pair of shoes for the workers, or clothing, or coal is, of course-is made to assist in the war effort. That has nothing to do with the old conception, which has long since died out, and which we find in the Geneva Prisoner of War Convention. I was at the Krupp plant five or six times ... when I went to visit these plants, it was mostly in order to see how we could do away with the consequences of air attacks. It was always shortly after air raids, and so I got an idea of the production. As I worked hard I knew a lot about these problems, right down to the details. Of course, Krupp had labor camps. I cannot give the percentage, but no doubt Krupp did employ foreign workers and prisoners of war. I do not know the details. I do not know the figures of how many workers Krupp employed in all. I am not familiar with them at the moment. But I believe that the percentage of foreign workers at Krupp was about the same as in other plants and in other armament concerns.

That [the percentage of foreign workers] varied a great deal. The old established industries which had their old regular personnel had a much lower percentage of foreign workers than the new industries which had just grown up and which had no old regular personnel. The reason for this was that the young age groups were drafted into the Armed Forces and therefore the concerns which had a personnel of older workers still retained a large percentage of the older workers. Therefore the percentage of foreign workers in Army armaments, if you take it as a whole and as one of the older industries, was lower than the percentage of foreign workers in air armaments, because that was a completely new industry which had no old regular personnel. But with the best will in the world I cannot give you the percentage.

From Speers' Nuremberg Draft [a fifty-nine page profile of Hitler's regime drafted by Speer while a prisoner at Eisenhower's HQ in 1945]: One thing is certain: All those who worked closely with him were to an extraordinary degree dependent on and servile to him. However powerful they appeared in their domain, in his proximity they became small and timid . . . .

In the autumn of 1943, after a visit to Fuehrer HQ, Doenitz and I once discussed this hypnotic quality of his. And we realized that both of us had reduced our attendance at Fuehrer HQ to once every few weeks for the same reason: to maintain our inner independence. Both of us were certain that we could no longer function properly if, like Keitel for example, we were continuously near him. We were sorry for Keitel who was so much under his influence that he was finally nothing but his tool, without any will of his own.

From Messerschmitt's US SBS interview: It was Professor Messerschmitt's opinion that area attacks on cities did no critical damage to war production and that they resulted in a stiffening of morale. (SBS)

From Speer's IMT testimony: It must have been toward the end of 1943 . . . . It was at the Fuehrer's headquarters in East Prussia in front of Goering's train. Galland had reported to Hitler that enemy fighter planes were already escorting bomber squadrons as far as Liege and that it was to be expected that in the future the bomber units would travel still farther from their bases escorted by fighters. After a discussion with Hitler on the military situation Goering upbraided Galland and told him with some excitement that this could not possibly be true, that the fighters could not go as far as Liege. He said that from his experience as an old fighter pilot he knew this perfectly well. Thereupon Galland replied that the fighters were being shot down, and were lying on the ground near Liege. Goering would not believe this was true. Galland was an outspoken man who told Goering his opinion quite clearly and refused to allow Goering's excitement to influence him.

Finally Goering, as Supreme Commander of the Air Force, expressly forbade Galland to make any further reports on this matter. It was impossible, he said, that enemy fighters could penetrate so deeply in the direction of Germany, and so he ordered him to accept that as being true. I continued to discuss the matter afterward with Galland and Galland was actually later relieved by Goering of his duties as Commanding General of Fighters. Up to this time Galland had been in charge of all the fighter units in Germany. He was the general in charge of all the fighters within the High Command of the Air Force.

From Speer's US SBS interview: Later on I had an opportunity to witness the effects of numerous night attacks on Berlin for the period from about June, July 1943 until February 1944. Those, though they always had considerable effect, speedily hardened the population. They did not mind air attacks very much any longer. The effects of industry were indirect only in that labor first remained absent for a few days in those plants not directly hit. But one must say that the German worker possesses an extraordinary resistance and up to the end, and in spite of air attacks, returned to the plants and worked again. I for my part had always to underline that we owe our achievements almost exclusively to our German Workers. Attacks against towns or city centers can only make sense if the nations do not have the necessary resistance. (SBS)

December 10, 1943: Albert Speer visits the Nordhausen Mittelwerk V-2 rocket plant at Camp Dora. (Sellier, IMT)From Speer's IMT testimony: The [labor] program was extended to Belgium, Holland, Italy, and Czechoslovakia. The entire production in these countries was also declared blocked, and the laborers in these blocked industries were given the same protection as in France, even after the meeting with Hitler on 4 January 1944, during which the new program for the West for 1944 was fixed. I adhered to this policy. The result was that during the first half of 1944, 33,000 workers came from France to Germany as compared with 500,000, proposed during that conference; and from other countries, too, only about 10 percent of the proposed workers were taken to Germany.

His [Hitler's] decision was a useless compromise, as was often the case with Hitler. These blocked factories were to be maintained, and for this purpose Sauckel was given the order to obtain 3,500,000 workers from the occupied territories. Hitler gave the strictest instructions through the High Command of the Armed Forces to the military commanders that Sauckel's request should be met by all means. Contrary to the Fuehrer's decision during that meeting, I informed the military commander of the way I wanted it, so that in connection with the expected order from the High Command of the Armed Forces the military commander would have two interpretations of the meeting in his hands. Since the military commander was agreeable to my interpretation, it could be expected that he would follow my line of thought.

From Speer's IMT testimony: I should like to summarize the entire subject and say a few words about it. We had a technique of dealing with inconvenient orders from Hitler that permitted us to by-pass them. Jodl has already said in his testimony that for his part he had developed such a technique too. And so, of course, the letters which are being submitted here are only clear to the expert as to their meaning and the results they would have to have.

January 7, 1944: Speer and Milch meets with Hitler at his headquarters. The Fuehrer informs them that analysis of English periodicals reveals that the English are near to achieving success in the testing of experimental jet aircraft. Hitler demands that production of the Me 262, the Germans' turbojet fighter aircraft, be put on top priority.From Speer's US SBS interview: Several times the bombs came close, but with Siemensstadt we always had incredible luck. Despite the many raids we never had a collapse of production, but this was an exceptional case. This was because Siemens has high concrete buildings which can be totally destroyed with heavy bombs. With medium or small caliber’s it sometimes happened that if the bombs hit the top a few upper floors were destroyed and we could continue to work downstairs. Concrete buildings are generally very good as air raid protection. (SBS)

February 18, 1944: Most Honored Reich Marshal:From Speer's IMT testimony: I received the letter on or about 15 May in Berlin, when I returned after my illness. Its contents greatly upset me because, after all, this is nothing more than kidnapping. I had an estimate submitted to me about the number of people thus being removed from the economic system. The round figure was 30,000 to 40,000 a month. The result was my declaration in the Central Planning Board on 22 May 1944, where I demanded that these workers, even as internees, as I called them, should be returned to their old factories at once. This remark, as such, is not logical because, naturally, the number of crimes in each individual factory was very low, so that such a measure was not practicable. Anyhow, what I wished to express by it was that the workers would have to be returned to their original places of work. This statement in the Central Planning Board has been submitted by the Prosecution.

Immediately after the meeting of the Central Planning Board I went to see Hitler, and there I had a conference on 5 June 1944. The minutes of the Fuehrer conference are available. I stated that I would not stand for any such procedure, and I cited many arguments founded entirely on reason, since no other arguments would have been effective. Hitler declared, as the minutes show, that these workers would have to be returned to their former work at once, and that after a conference between Himmler and myself he would once again communicate this decision of his to Himmler.

From Sauckel's IMT testimony: I did not deny that there was collaboration. Collaboration is necessary in every regime and in every system. Here we were not concerned with foreign labor only, but chiefly with German labor, even at that period. I did not dispute the fact that work was being carried on; but final decisions were not always made there. That is what I wanted to say. I did not have representatives in the various administrative departments. I had liaison men, or else the administrative departments had liaison men in my office. The man who was constantly with Speer was not a liaison officer, but the man who talked over with the Minister questions of demand, et cetera, which were pending. As far as I remember it was a Herr Berk.

From Speer's IMT testimony: In 1941 I had not yet anything to do with armament; and even later, during the period of Sauckel's activity, I did not appoint these delegates and did not do much to promote their activities. That was a matter for Sauckel to handle; it was in his jurisdiction. In 1943 I demanded in the Central Planning Board that the German labor reserves should be drawn upon, and in 1944 during the conversation of 4 January with Hitler I said the same thing. Sauckel at that time stated--and that can be seen from his speech of 1 March 1944, which has been submitted as a document--that there were no longer any reserves of German workers.

But at the same time he also testified here that he had succeeded in 1944 in mobilizing a further 2 million workers from Germany, whereas at a conference with Hitler on 1 January 1944 he considered that to be completely impossible. Thus he has himself proved here that at a time when I desired the use of internal labor he did not think there was any, although he was later forced by circumstances to mobilize these workers from Germany after all; therefore my statement at the time was right.

From Speer's IMT testimony: Up to the spring of 1943 I completely endorsed them. Up to that time no obvious disadvantages had resulted for me. However, beginning with the spring of 1943, workers from the West refused in ever-increasing numbers to go to Germany. That may have had something to do with our defeat at Stalingrad and with the intensified air attacks on Germany. Up to the spring of 1943, to my knowledge, the labor obligations were met with more or less good will. However, beginning with the spring of 1943, frequently only part of the workers who had been called up came to report at the recruiting places.

Therefore, approximately since June 1943, I established the so-called blocked factories through the military commanders in France. Belgium, Holland, and Italy soon followed suit in establishing these blocked industries. It is important to note that every worker employed in one of these blocked factories was automatically excluded from allocation to Germany; and any worker who was recruited for Germany was free to go into a blocked factory in his own country without the labor allocation authorities having the possibility of taking him out of this blocked factory.

After the establishment of the blocked factories, the labor allocation from the occupied countries in the West to Germany decreased to a fraction of what it had been. Before that between 80,000 and 100,000 workers came for instance from France to Germany every month. After the establishment of the blocked factories, this figure decreased to the insignificant number of 3,000 or 4,000 a month, as is evident from Document RF-22. It is obvious, and we have to state the facts, that the decrease in these figures was also due to the resistance movement which began to expand in the West at that time.

At that time the first serious difference arose about the "blocking" of these workers from labor allocation in Germany. This came about through the fact that the loss of laborers, which I had in the production in the occupied countries, was larger than the number of workers who came to Germany from the occupied countries of the West. According to it perhaps 400,000 workers came from France to Germany in 1943, especially during the first half of the year. Industrial workers in France, however, decreased by 800,000, and the French workers in France who worked for Germany decreased by 450,000.

According to my opinion there was still a considerable latent reserve in the German production, since the German peace economy had not been converted into a war economy on a sufficiently large scale. Here was, in my opinion, next to the German women workers, the largest reserve of the German home labor supply.

At that time, I had already worked out the following plan. A large part of the industry in Germany produced so-called consumer goods. Consumer goods were, for instance, shoes, clothing, furniture, and other necessary articles for the Armed Forces and for the civilian requirements. In the occupied western territories, however, the industries which supplied these products were kept idle, as the raw materials were lacking. But they nevertheless had a great potential. In carrying through this plan I deprived German industries of the raw materials which were produced in Germany, such as synthetic wool, and sent them to the West. Thereby, in the long run, a million more workers could be supplied with work in the country itself; and thus I obtained 1 million German workers for armament. All these plans failed. Before the outbreak of war the French Government did not succeed in building up armament production in France, and I also failed, or rather my agencies failed, in this task.

Through this plan I could close down whole factories in Germany for armament; and in that way I freed not only workers, but also factory space and administrative personnel. I also saved on electricity and transportation. Apart from that, since these factories had never been of importance for the war effort they had received hardly any foreign workers; and thus I almost exclusively obtained German workers for the German production, workers, of course, who were much more valuable than any foreign workers.

The disadvantages were considerable, since any closing down of a factory meant the taking out of machinery, and at the end of the war a re-conversion to peacetime production would take at least 6 to 8 months. At that time, at a Gauleiter meeting at Posen, I said that if we wanted to be successful in this war, we would have to be those to make the greater sacrifices.

From Hermann Goering's US SBS interview: The first aircraft were primarily experimental ships and their engines had a lifetime of about four to five hours. Then again, they were completely new machines of which a great number had to be used for the training of pilots. Furthermore, we had to shake out the 'bugs' from the engines. So that a lot of the first machines were lost through forced landings. Another thing, the ship had a kind of brake which had to be applied very carefully, otherwise it would roll off the runway and until we had corrected that, we lost a number of machines this way. It was hard to throttle it back because it was very fast. A lot of other things came into it. It was just a completely new ship and a completely new type of engine. But toward the end, everything was under control, and what was needed was a little more experience for the pilots, so that they might know how to fly this ship at its high speeds...The Fuehrer had originally directed that it be produced as a fighter, but in May, 1944, he ordered that it be converted into a fighter-bomber. This conversion was one of the main reasons for the delay in getting this plane into action in any quantity. (SBS)

May 7, 1944: From a letter from office chief Schieber to Speer:From Speer's IMT testimony: The "Hiwi" mentioned in the document are the so-called auxiliary volunteers who had joined the troops fighting in Russia. As the months went by, they took on large proportions, and during the retreat they followed along, as they would probably have been treated as traitors in their own country. These volunteers were not, however, as I desired it, put into industry, since the conference that was planned did not take place.

May 29, 1944: Speer writes to Jodl:From Speer's IMT testimony: I should like to say that I wanted a delegate to deal with all labor allocation problems connected with my task of military armament production. My chief concern in the allocation problem, at the beginning of my term of office, was with the Gauleiter, who carried on a policy of Gau particularism. The nonpolitical offices of the Labor Ministry could not proceed against the Gauleiter, and the result was that manpower inside Germany was frozen. I suggested to Hitler that he should appoint a Gauleiter whom I knew to this post-a man named Hanke. Goering, by the way, has already confirmed this. Hitler agreed. Two days later, Bormann made the suggestion that Sauckel be chosen. I did not know Sauckel well, but I was quite ready to accept the choice. It is quite possible that Sauckel did not know. anything about the affair and that he assumed--as he was entitled to do--that he was chosen at my suggestion.

The office of the Plenipotentiary General for the Allocation of Labor was created in the following way: Lammers declared that he could not issue special authority for a fraction of labor allocation as that would be doubtful procedure from an administrative point of view, and for that reason the whole question of manpower would have to be put into the hands of a plenipotentiary. At first they contemplated a Fuehrer decree. Goering protested on the grounds that it was his task under the Four Year Plan. A compromise was made, therefore, in accordance with which Sauckel was to be the Plenipotentiary General within the framework of the Four Year Plan, although he would be appointed by Hitler. This was a unique arrangement under the Four Year Plan. Thereby Sauckel was in effect subordinated to Hitler; and he always looked upon it in that way.

From Speer's IMT testimony: Immediately after this conference I went to see Himmler and communicated to him Hitler's decision. He told me that no such number had ever been arrested by the Police. But he promised me that he would immediately issue a decree which would correspond to Hitler's demands; namely, that the SS would no longer be permitted to detain these workers. I informed Hitler of this result, and I asked him once more to get in touch with Himmler about it. In those days I had no reason to mistrust Himmler's promise because, after all, it is not customary for Reich Ministers to distrust each other so much. But anyhow, I did not have any further complaints from my assistants concerning this affair. I must emphasize that the settling of the entire matter was not really my affair, but the information appeared so incredible to me that I intervened at once. Had I known that already 18 months before Himmler had started a very similar action, and that in this letter, which has been submitted here.

Had I known this letter, I would never have had enough confidence in Himmler to expect that he would correctly execute his order as instructed by Hitler. For this letter shows quite clearly that this action was to be kept secret from other offices. These other offices could only be the of lice of the Plenipotentiary General for the Allocation of Labor or my own office.

Finally, I want to say in connection with this problem that it was my duty as Minister for Armament to put to use as many workers as were possibly available for armaments production, or any other production. I considered it proper, therefore, that workers from concentration camps, too, should work in war production or armament industries. The main accusation by the Prosecution, however, that I deliberately increased the number of concentration camps, or caused them to be increased, is by no means correct. On the contrary I wanted just the opposite, looking at it from my point of view of production.

At a Gauleiter meeting in the summer of 1944 Hitler had already stated-and Schirach is my witness for this-that if the German people were to be defeated in the struggle it must have been too weak, it had failed to prove its mettle before history and was destined only to destruction. Now, in the hopeless situation existing in January and February 1945, Hitler made remarks which showed that these earlier statements had not been mere flowers of rhetoric. During this period he attributed the outcome of the war in an increasing degree to the failure of the German people, but he never blamed himself. He criticized severely this alleged failure of our people who made so many brave sacrifices in this war.

From Speer's IMT testimony: From August 1944 [I used my influence to prevent destruction in the occupied countries], in the industrial installations in the Government General, the ore mines in the Balkans, the nickel works in Finland; from September 1944, in the industrial installations in Upper Italy; beginning with February 1945, in the oil fields in Hungary and the industries of Czechoslovakia. I should like to emphasize in this connection that I was supported to a great extent by Generaloberst Jodl, who quietly tolerated this policy of non-destruction. As far as industries were concerned, those executive powers [to carry out orders of destruction] were vested in me. Bridges, locks, railroad installations, et cetera, were the affair of the Wehrmacht. The industrial region of Upper Silesia, the remaining districts of Poland, Bohemia and Moravia, Alsace-Lorraine, and Austria, of course, were protected against destruction in the same way as the German areas. I made the necessary arrangements by personal directives on the spot-particularly in the Eastern Territories.

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

>

Disclaimer: The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Fair Use Notice: The Propagander!™may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.